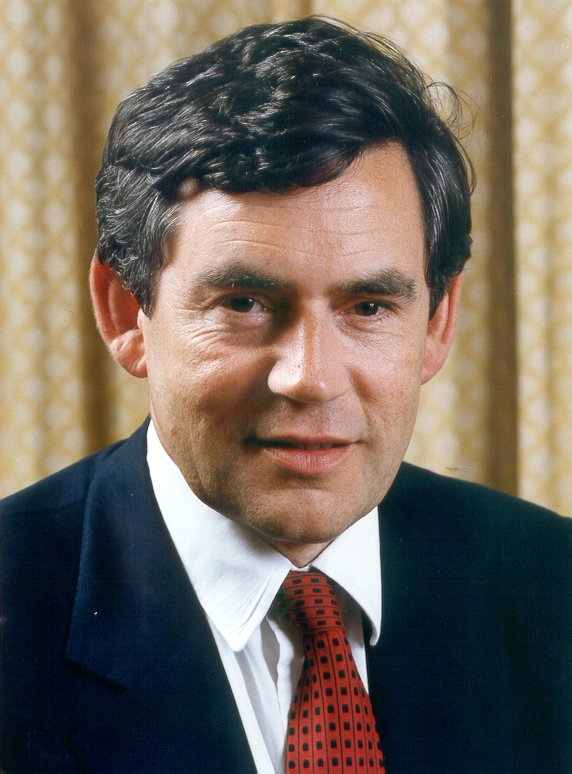

By Richard Norman

A few interesting things about Gordon Brown today (actually from a few weeks ago). This series of articles in Prospect Magazine about Brown as intellectual are worth looking at for those interested in his background and philosophical evolution over the years. There’s something for both people who like him and dislike him. Some quotes after the jump. From John Lloyd:

A few interesting things about Gordon Brown today (actually from a few weeks ago). This series of articles in Prospect Magazine about Brown as intellectual are worth looking at for those interested in his background and philosophical evolution over the years. There’s something for both people who like him and dislike him. Some quotes after the jump. From John Lloyd:

Connectedness is a consistent theme. Brown’s sense of a threat of a moral breakdown at both the individual and the social level has led him to search through the work of thinkers who share that view?who have been mainly, in recent times, of the political right. The modern left, especially since the 1960s, has been often scornful of a morality it regarded as "bourgeois," and even while calling for extreme forms of collectivism has in practice endorsed much of the libertarian individualism of contemporary consumerism. The right, by contrast, has tended to ring the bell to warn of an approaching social leprosy; and none more cogently than two of Brown’s favourite thinkers?the political scientist James Q Wilson and the philosopher Gertrude Himmelfarb?both American, and both of whom Brown has invited to give seminars at No 11 Downing Street. In The Moral Sense (1993), Wilson argues that the indulgence, cruelty and violence that is now a familiar part of life has been the fault of those who too weakly, or apologetically, maintain moral-social limits, and says that "how vigorously and persuasively we?mostly but not entirely older people?assert those limits will surely depend to some important degree on how confidently we believe in the sentiments that underlie them. Some of us have lost that confidence. The avant garde in music, art and literature mocks that confidence." Himmelfarb, a historian of ideas, sees in the British Enlightenment a "sociology of virtue" (the Scots Enlightenment was, for a time, the most important part of the British phenomenon?a source of inspiration and of pride for the Edinburgh-educated Brown). She sees in the world of David Hume, Adam Smith and others the same kind of search as that in which Brown is said to be engaged: a quest for a robust social morality. She quotes Smith’s "left-wing" Theory of Moral Sentiments?now much less well known than his "right-wing" Wealth of Nations?and argues that Smith locates altruism?social morality?in human nature itself.

From Daniel Johnson:

By the standards of all but the most recent British politicians, Brown’s bookish tastes are nothing out of the ordinary. Victorian men of letters routinely went into politics: Gladstone, who had mastered the entire culture of his time, or Disraeli, whose novels are still read for their literary merit. The last of these scholar-statesmen was Churchill, who actually won the Nobel prize for literature. Among Labour leaders, Hugh Gaitskell, Harold Wilson and Michael Foot were intellectuals, though only the last rejoiced in the appellation. On the strength of Brown’s summer reading list (Sebastian Faulks, Thomas Keneally, JK Rowling), a Roy Jenkins or a Keith Joseph would have thought him distinctly middlebrow. His reading, though omnivorous, is lacking in cosmopolitan culture. True, Brown says he reads Camus and Sartre for pleasure. The intellectuals of the previous generation, though, would have read them in the original language, and other, more daunting, foreign authors too. Dick Crossman made his name with a book on Plato; Enoch Powell was the youngest professor of ancient Greek since Nietzsche. By comparison, Brown’s frame of reference is provincial. Unlike his intellectual superiors, however, he has climbed the greasy pole to the very top. Gordon Brown is an intellectual of a very Scottish type. This figure is most often identified as a "dominie" (schoolmaster or minister) or a "son of the manse" (which Brown is). He is overbearingly didactic, in part to disguise his own self-conscious autodidacticism. He is pugnacious, even disputatious; austere, even lugubrious; and manly to the point of misogyny. After all, the archetypal Scottish intellectual was John Knox author of First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women.

From Geoff Mulgan:

Here we come to another of the defining characteristics of Brownism. His sources of influence are very American, or to be more precise, northeast American, drawn from an academic culture where rigorous rationalist Enlightenment thought has fused with a vigorous Protestantism. Robert Putnam, Howard Gardner and Francis Fukuyama are all examples, as is Thomas Friedman. Californian thinking has had much less influence, new-age ideas none. Nor is there much evidence of influences from Europe (no Habermas or Bourdieu), or Asia (with the partial exception of Amartya Sen), or Latin America (no Roberto Unger or Paolo Freiere). This American liberal republican tradition has many virtues, including a strong sense of history and of moral purpose. It is a modern equivalent to the milieu of the 18th-century Edinburgh Enlightenment, and the world of figures like Adam Smith and James Ferguson, and it has continued to innovate. Through figures like Cass Sunstein, the American liberal republican tradition has started to address the subtle questions of behaviour and culture which look set to dominate the politics of the next few decades: how do you persuade people to do the right things, whether in relation to their own health, climate change or simply in behaving considerately to their fellow citizens. Yet this tradition also has its share of blind spots. It’s been slow to engage with the environment or gender. It’s not much interested in science, except as a problem; and it’s oddly parochial (you can look in vain for any suggestion that the nine tenths of the world’s population outside Europe and north America have ever had any original insights).

-Richard