By Richard Norman

Within six days, Israel had tripled the territory under its control. It had humiliated its most intimidating neighbours. It had gained control over a number of the most important Jewish holy sites. Not only had Israelis survived a threat which only a few weeks earlier had precipitated the consecration of public parks and stadia as potential mass burying grounds, but they had decimated their enemies. How had the Arab states so badly misjudged their position in the buildup to war? Not unsurprisingly, Nasser saw Egypt’s national security through the lens of the 1956 Suez Crisis (in which Egypt had been attacked by the UK, France, and Israel almost simultaneously). Now that Egypt was a client of the Soviet Union, the USA could be added firmly to this camp of enemies. It was the Western powers, the "wider conspiracy" against the Arab people, that propped up an essentially weak Israel. Now it was 1967, and with the Soviets supporting the Arabs, and the Americans tied up in Vietnam, Nasser believed the Johnson administration would be unlikely to give support to Israel should a war break out (particularly if Israel started it). But geopolitical concerns were only part of Nasser’s thinking (or lack of thinking) on the issue. Base psychology played a role. Surely, like all illegitimate regimes, Israel would collapse when dealt a righteous blow. Uncompromisingly committed to his mode of reasoning, Nasser twisted counter-evidence to fit his narrative. Even Israeli Prime Minister Eshkol’s messages "seeking to avert war, and emphasizing the role of the international community, had been interpreted [by the Egyptians] as further evidence of Israeli military inferiority and unwillingness to take independent action" [James, MERIA] To top it all off, a propagandistic media, essentially an echo chamber for Nasser’s ego, encouraged this climate of misjudgment among the Egyptian elite. For Syria and Jordan, both of whom had military pacts with Egypt and were committed to their powerful partner, the situation was broadly similar (though King Hussein was forced into the conflict more out of domestic considerations than out of concerns mirroring Nasser’s). But was the war actually caused by Nasser’s brinksmanship? Were Egypt’s actions in May 1967 simply the recklessness of a delusional and aggressive policy? Recent scholarship puts the conflict in the broader context of the Cold War, and gives the Soviet Union pride of place as chief instigator.

Coinciding with the 40th anniversary of the war, Foxbats over Dimona: The Soviets’ Nuclear Gamble in the Six-Day War, by Remez and Isabella Ginor, is to be published by Yale University Press early next month. The title refers to the Soviets’ most advanced fighter plane, the MiG-25 Foxbat, which the authors say flew sorties over Dimona shortly before the Six Day War, both to help bolster the Soviet effort to encourage Israel to launch a war, and to ensure the nuclear target could be effectively destroyed once Israel, branded an aggressor for its preemption, came under joint Arab-Soviet counterattack. Soviet nuclear-missile submarines were also said to have been poised off Israel’s shore, ready to strike back in case Israel already had a nuclear device and sought to use it. The Soviets’ intended central intervention in the war was thwarted, however, by the overwhelming nature of the initial Israeli success, the authors write, as Israel’s preemption, far from weakening its international legitimacy and exposing it to devastating counterattack, proved decisive in determining the conflict. And because the Soviet Union’s plan thus proved unworkable, the authors go on, its role in stoking the crisis, and its plans to subsequently remake the Middle East to its advantage, have remained overlooked, undervalued or simply unknown to historians assessing the war over the past 40 years. [Jerusalem Post. More on the subject can be found here]

Much of the climate of opinion on this fortieth anniversary suggests that the Israeli victory in 1967 was "wasted" (in the words of the Economist, for example). Some writers have quoted Wellington, that "the only thing worse than a great victory is a great defeat." The West Bank Israeli settlements and oppression of the Palestinian people are seen as the ultimate and deplorable result of the war. The line of reasoning argues that emboldened and inspired by a spectacular victory, Israelis began to feel increasingly entitled and chauvinistic. The truth, I think, is somewhat different. Those who lost the 1967 war–Egypt, Jordan, Syria–did not sue for the peaceful return of their territories (which Israel was willing to return in the aftermath[see also the BBC documentary mentioned in part 1). Indeed, these states were unwilling to accept peace or negotiations of any sort, and continued to make statements threatening to put an end to the very existence of Israel. Indeed, on September 1, 1967, at the Khartoum Arab Summit, the Arab states laid out their position regarding the disputed territories:

1. No peace with Israel 2. No recognition of Israel 3. No negotiations with Israel

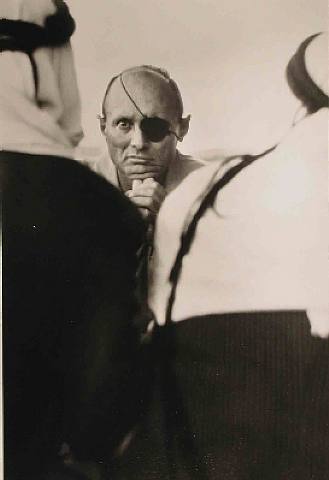

Given the opportunity to trade land for peace, Israel has done so (the Sinai was returned to Egypt in 1979). But when the avenues of negotiation are closed and calls for the destruction of the Israeli people are mainstream, who is a partner for peace? Even now, the ruling party of the Palestinian government essentially endorses the three "No’s" of the Khartoum Summit. Who is the partner in peace? The Palestinian people are among the world’s most deeply unfortunate:betrayed by their leaders, a pawn (at best) of Arab governments, confined to ghettos and camps as a permanent stateless underclass. But to suggest that Israel has been their sole nemesis or that Israeli efforts at self-defence are illegitimate because of the collateral damage done to the Palestinian people is unreasonable. Expansionism/chauvinism have not been the guiding principles of Israeli policy throughout its existence–its guiding principle has been security. Those leaders and states who have called for its destruction, who have employed terrorism (the intentional murder of civilians), who have sought to blame "wider conspiracies" for their own failings, are largely responsible for the status quo, the continuing aftermath of war of 1967. Above: Moshe Dayan at the Kalandiya refugee camp in 1967. (Picture by Micha Bar-Am.) -Richard

Thanks for the comment! Yes, I agree it is entirely possible to do damage to one’s security by acting out of all proportion or incompetently when trying to defend oneself. I’m not supporting every action Israel has ever taken, I’m arguing that on balance Israel’s actions in self-defence have been in their long term security interests (for example, who would have imagined after so many wars Israel would have suffered so little–relative to what might have been [for example 21 times less casualties than their adversaries in the 1967 war]) and I think that on balance their efforts at self-defence have been designed to minimize civilians deaths, which is the exact opposite policy of Hamas, Hezbollah, etc, (or Syria, for example, during the 67 war or Saddam during the Gulf War, etc, etc). To me this whole conflict comes down to the deliberate targeting of civilian populations. Israel doesn’t do it; its enemies do. Nevertheless, I agree there are notable exceptions of Israel behaving irresponsibly, against their interests. It is to the credit of the Israeli people that these exceptions are discussed and corrective action demanded (although Olmert still clings to power with [as of April] a 2% approval rating). And I also agree that West Bank settlements are a serious impediment to peace.

“[to suggest] that Israeli efforts at self-defence are illegitimate because of the collateral damage done to the Palestinian people is unreasonable.”

Just to clarify, you are referring to certain specific actions and not every action Israel has undertaken in the name of self-defence, right? I have always thought the problem is not the right to self-defense, but the best way to carry it out with a goal towards long-term security. I actually think the security wall is a great idea, since by diminishing the number of suicide bombings it has also greatly reduced retaliation againt the Palestinians. I just think that sometimes the Israeli government takes actions (e.g. increasing settlement activity on the West Bank, the summer war with Lebanon) that undermine its own security, and I ask why? Fortunately, a lot of Israelis agree with me, at least after the fact (just like Americans on the Iraq war). Sometimes naive pacifism works well in hindsight…