On Monday, June 16th of 2008 same-sex marriage became legal in the state of California due to a ruling by the Supreme Court of California. Since this site is crawling with human rights lawyers and such I will not embarrass myself by attempting detailed legal analysis of the 172 page ruling but I think the decision is worthy of comment. While the state of Massachusetts had already legalized same-sex marriages back in 2004, and Connecticut, Vermont, New Jersey, and New Hampshire all had civil union laws with equal benefits, this case was particularly significant for several reasons. California is the largest state in the nation and also possesses the highest population of same-sex couples (over 92,000 according to the 2000 census), the largest gay population at over 1.3 million, and the most famous “Gay village” in the world, San Francisco, which has a gay population as high as 15%.

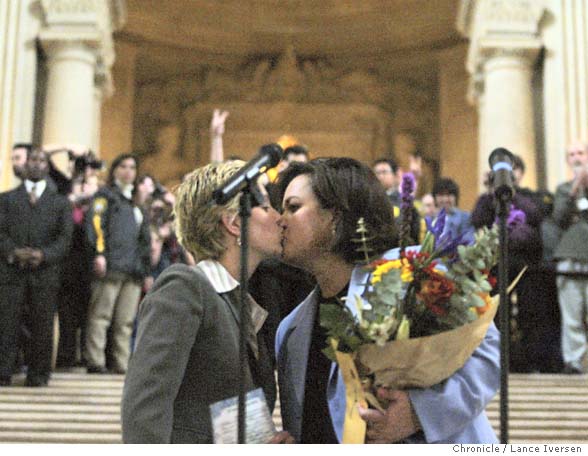

Perhaps more significant is the fact that the court’s ruling is the first to overturn the California Defense of Marriage Act emobdied in Proposition 22, the Ballot initiative approved by California voters by about 61% to 39% in a 2000 referendum. Proposition 22 , just 14 words long, states “Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.” The interesting thing about this ballot initiative is that it constituted a response to California’s Domestic Partnership Laws. Proponents of Proposition 22 feared that these laws, which gave same-sex couples with registered domestic partnerships the same legal rights (at the state level) to adoption, inheritance, hospital visitations, etc. as married heterosexual couples would open the door to gay marriage. Obviously many proponents of Proposition 22 rejected the idea of domestic partnerships as well, but the court of appeals had rejected attempts to overrule these laws, enacted by the legislature. Proposition 22 was their way of attempting to prevent future administrations or legislators from granting the name “marriage” to these domestic partnerships. In 2004, progressive San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsome began performing marriage ceremonies for same-sex couples at City Hall – these marriages were quickly annulled by the California courts, leading to an appeal launched by the City of San Francisco and others. (Newsome himself is not gay, at least based on his recent affair with the wife of the manager of his re-election campaign). This led us to the recent 4-3 ruling on May 16th, 2008 that opened the door to the first officially recognized state marriages on June 16th 2008.

Because California already recognized many of the legal rights of same sex couples, the case was primarily argued on the basis of nomenclature – whether disallowing same-sex couples from using the word “marriage” to describe their relationship constituted discrimination under the California constitution. CJ George, author of the majority opinion, writes:

Accordingly, the legal issue we must resolve is not whether it would be constitutionally permissible under the California Constitution for the state to limit marriage only to opposite-sex couples while denying same-sex couples any opportunity to enter into an official relationship with all or virtually all of the same substantive attributes, but rather whether our state Constitution prohibits the state from establishing a statutory scheme in which both opposite-sex and same-sex couples are granted the right to enter into an officially recognized family relationship that affords all of the significant legal rights and obligations traditionally associated under state law with the institution of marriage, but under which the union of an opposite-sex couple is officially designated a “marriage” whereas the union of a same-sex couple is officially designated a “domestic partnership.” The question we must address is whether, under these circumstances, the failure to designate the official relationship of same-sex couples as marriage violates the California Constitution.

It also is important to understand at the outset that our task in this proceeding is not to decide whether we believe, as a matter of policy, that the officially recognized relationship of a same-sex couple should be designated amarriage rather than a domestic partnership (or some other term), but instead only to determine whether the difference in the official names of the relationships violates the California Constitution. We are aware, of course, that very strongly held differences of opinion exist on the matter of policy, with those persons who support the inclusion of same-sex unions within the definition of marriage maintaining that it is unfair to same-sex couples and potentially detrimental to the fiscal interests of the state and its economic institutions to reserve the designation of marriage solely for opposite-sex couples, and others asserting that it is vitally important to preserve the long-standing and traditional definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman, even as the state extends comparable rights and responsibilities to committed same-sex couples. Whatever our views as individuals with regard to this question as a matter of policy, we recognize as judges and as a court our responsibility to limit our consideration of the question to a determination of the constitutional validity of the current legislative provisions.

After rejecting the idea that same-sex marriage could be justified on the basis of constitutional protections against discrimination on the basis of gender, CJ George goes on to write the main reasons for the majority decision. Note in particular the language referring to “second class citizenship” and the reference to the Supreme Court of Canada ruling:

First, because of the long and celebrated history of the term “marriage” and the widespread understanding that this term describes a union unreservedly approved and favored by the community, there clearly is a considerable and undeniable symbolic importance to this designation. Thus, it is apparent that affording access to this designation exclusively to opposite-sex couples, while providing same-sex couples access to only a novel alternative designation, realistically must be viewed as constituting significantly unequal treatment to same-sex couples. In this regard, plaintiffs persuasively invoke by analogy the decisions of the United States Supreme Court finding inadequate a state’s creation of a separate law school for Black students rather than granting such students access to the University of Texas Law School and a state’s founding of a separate military program for women rather than admitting women to the Virginia Military Institute. As plaintiffs maintain, these high court decisions demonstrate that even when the state grants ostensibly equal benefits to a previously excluded class through the creation of a new institution, the intangible symbolic differences that remain often are constitutionally significant.

Second, particularly in light of the historic disparagement of and discrimination against gay persons, there is a very significant risk that retaining a distinction in nomenclature with regard to this most fundamental of relationships whereby the term “marriage” is denied only to same-sex couples inevitably will cause the new parallel institution that has been made available to those couples to be viewed as of a lesser stature than marriage and, in effect, as a mark of second-class citizenship. As the Canada Supreme Court observed in an analogous context: “One factor which may demonstrate that legislation that treats a claimant differently has the effect of demeaning the claimant’s dignity is the existence of pre-existing disadvantage, stereotyping, prejudice, or vulnerability experienced by the individual or group at issue. . . It is logical to conclude that, in most cases, further differential treatment will contribute to the perpetuation or promotion of their unfair social characterization, and will have a more severe impact upon them, since they are already vulnerable.”

Third, it also is significant that although the meaning of the term “marriage” is well understood by the public generally, the status of domestic partnership is not. While it is true that this circumstance may change over time, it is difficult to deny that the unfamiliarity of the term “domestic partnership” is likely, for a considerable period of time, to pose significant difficulties and complications for same-sex couples, and perhaps most poignantly for their children, that would not be presented if, like opposite-sex couples, same-sex couples were permitted access to the established and well-understood family relationship of marriage.

Summing up, he writes:

Under these circumstances, we conclude that the distinction drawn by the current California statutes between the designation of the family relationship available to opposite-sex couples and the designation available to same-sex couples impinges upon the fundamental interest of same-sex couples in having their official family relationship accorded dignity and respect equal to that conferred upon the family relationship of opposite-sex couples.

In addition, plaintiffs’ briefs disclose a further way in which the different designations established by the current statutes impinge upon the constitutionally protected privacy interest of same-sex couples. Plaintiffs point out that one consequence of the coexistence of two parallel types of familial relationship is that – in the numerous everyday social, employment, and governmental settings in which an individual is asked whether he or she “is married or single” – an individual who is a domestic partner and who accurately responds to the question by disclosing that status will (as a realistic matter) be disclosing his or her homosexual orientation, even if he or she would rather not do so under the circumstances and even if that information is totally irrelevant in the setting in question. Because the constitutional right of privacy ordinarily would protect an individual from having to disclose his or her sexual orientation under circumstances in which that information is irrelevant, the existence of two separate family designations – one available only to opposite-sex couples and the other to same-sex couples – impinges upon this privacy interest, and may expose gay individuals to detrimental treatment by those who continue to harbor prejudices that have been rejected by California society at large.

For all of these reasons, we conclude that the classifications and differential treatment embodied in the relevant statutes significantly impinge upon the fundamental interests of same-sex couples, and accordingly provide a further reason requiring that the statutory provisions properly be evaluated under the strict scrutiny standard of review…

While retention of the limitation of marriage to opposite-sex couples is not needed to preserve the rights and benefits of opposite-sex couples, the exclusion of same-sex couples from the designation of marriage works a real and appreciable harm upon same-sex couples and their children. As discussed above, because of the long and celebrated history of the term “marriage” and the widespread vunderstanding that this word describes a family relationship unreservedly sanctioned by the community, the statutory provisions that continue to limit access to this designation exclusively to opposite-sex couples – while providing only a novel, alternative institution for same-sex couples – likely will be viewed as an official statement that the family relationship of same-sex couples is not of comparable stature or equal dignity to the family relationship of opposite-sex couples. Furthermore, because of the historic disparagement of gay persons, the retention of a distinction in nomenclature by which the term “marriage” is withheld only from the family relationship of same-sex couples is all the more likely to cause the new parallel institution that has been established for same-sex couples to be considered a mark of second-class citizenship. Finally, in addition to the potential harm flowing from the lesser stature that is likely to be afforded to the family relationships of same-sex couples by designating them domestic partnerships, there exists a substantial risk that a judicial decision upholding the differential treatment of opposite-sex and same-sex couples would be understood as validating a more general proposition that our state by now has repudiated: that it is permissible, under the law, for society to treat gay individuals and same-sex couples differently from, and less favorably than, heterosexual individuals and opposite-sex couples.

In light of all of these circumstances, we conclude that retention of the traditional definition of marriage does not constitute a state interest sufficiently compelling, under the strict scrutiny equal protection standard, to justify withholding that status from same-sex couples.

In the dissenting opinion, J Baxter, in addition to arguing that gay marriage should be brought about through legislation and the will of the people rather than through the courts (citing the “separation of powers” argument popular in US constitutional law) makes a common counter argument to recognition of gay marriage based on the status of polygamous and incestuous marriages:

The majority opinion reflects considerable research, thought, and effort on a significant and sensitive case, and I actually agree with several of the majority’s conclusions. However, I cannot join the majority’s holding that the California Constitution gives same-sex couples a right to marry. In reaching this decision, I believe, the majority violates the separation of powers, and thereby commits profound error.

Only one other American state recognizes the right the majority announces today. So far, Congress, and virtually every court to consider the issue, has rejected it. Nothing in our Constitution, express or implicit, compels the majority’s startling conclusion that the age-old understanding of marriage – an understanding recently confirmed by an initiative law – is no longer valid. California statutes already recognize same-sex unions and grant them all the substantive legal rights this state can bestow. If there is to be a further sea change in the social and legal understanding of marriage itself, that evolution should occur by similar democratic means. The majority forecloses this ordinary democratic process, and, in doing so, oversteps its authority.

The majority’s mode of analysis is particularly troubling. The majority relies heavily on the Legislature’s adoption of progressive civil rights protections for gays and lesbians to find a constitutional right to same-sex marriage. In effect, the majority gives the Legislature indirectly power that body does not directly possess to amend the Constitution and repeal an initiative statute. I cannot subscribe to the majority’s reasoning, or to its result…

In a footnote, the majority insists that, though same-sex couples are included within the fundamental constitutional right to marry, the state’s absolute bans on marriages that are incestuous, or nonmonogamous are not in danger. Vaguely the majority declares that “[p]ast judicial decisions explain why our nation’s culture has considered [incestuous and polygamous] relationships inimical to the mutually supportive and healthy family relationships promoted by the constitutional right to marry.” Thus, the majority asserts, though a denial of same-sex marriage is no longer justified, “the state continues to have a strong and adequate justification for refusing to officially sanction polygamous or incestuous relationships because of their potentially detrimental effect on a sound family environment.

The bans on incestuous and polygamous marriages are ancient and deeprooted, and, as the majority suggests, they are supported by strong considerations of social policy. Our society abhors such relationships, and the notion that our laws could not forever prohibit them seems preposterous. Yet here, the majority overturns, in abrupt fashion, an initiative statute confirming the equally deeprooted assumption that marriage is a union of partners of the opposite sex. The majority does so by relying on its own assessment of contemporary community values, and by inserting in our Constitution an expanded definition of the right to marry that contravenes express statutory law. That approach creates the opportunity for further judicial extension of this perceived constitutional right into dangerous territory. Who can say that, in ten, fifteen, or twenty years, an activist court might not rely on the majority’s analysis to conclude, on the basis of a perceived evolution in community values, that the laws prohibiting polygamous and incestuous marriages were no longer constitutionally justified?

In no way do I equate same-sex unions with incestuous and polygamous relationships as a matter of social policy or social acceptance. California’s adoption of the DPA makes clear that our citizens find merit in the desires of gay and lesbian couples for legal recognition of their committed partnerships. Moreover, as I have said, I can foresee a time when the People might agree to assign the label marriage itself to such unions. It is unlikely, to say the least, that our society would ever confer such favor on incest and polygamy.

My point is that the majority’s approach has removed the sensitive issues surrounding same-sex marriage from their proper forum – the arena of legislative resolution – and risks opening the door to similar treatment of other, less deserving, claims of a right to marry. By thus moving the policy debate from the legislative process to the court, the majority engages in faulty constitutional analysis and violates the separation of powers.

I would avoid these difficulties by confirming clearly that there is no constitutional right to same-sex marriage. That is because marriage is, as it always has been, the right of a woman and an unrelated man to marry each other.

********************************************************************************************************************************************

Although the court ruling may have been mainly symbolic from the point of view of California residents who already had domestic partnerships, the ripple effect from the ruling is likely to be large for several reasons.

First, the ruling comes in the middle of an election season. In the 2004 election there were 11 states with ballot initiatives to ban same-sex at state level – in all 11 states the ballot measures passed by an overwhelming margin (between 58% and 86%) and strong conservative turnout in some of these states, particularly Ohio (which was the pivotal state in the 2004 election) is credited with giving George W Bush the 2004 election. While liberals and progressives in the US celebrate the triumph of gay marriage by lawsuit in Massachusetts and California, in many other states the issue is a powerful force for mobilizing the conservative base of the Republican party and putting more conservative lawmakers into Federal Office, where there is still no recognition of same-sex couples. At present, both the Democratic nominee Barack Obama and the Republican nominee John McCain oppose federal recognition of same-sex couples but also oppose a federal constitutional amendment that would ban same-sex marriage in all states. Both have at some stage supported civil unions, though McCain’s enthusiasm for civil unions has been considerably dampened by actually becoming the Republican nominee and having to win over the religious conservatives who make up the base of his party. If the California gay marriage decision becomes more of a national issue, McCain may seize the opportunity to change his old position that it be left to the states and take up support for a Constituional Amendment to ban same-sex marriage nationally, a wedge issue that would have considerable force in many states.

The second reason this decision is so important nationally is that the California ruling applies to anyone who visits the state, and not just residents (as was the case with the Massachusetts law). Some US gay couples already got married in Canada, and their marriages are recognized in the states of New Mexico, Rhode Island and New York despite the fact that gay marriage itself remains illegal in those states. The pressures are likely to mount as out-of-state couples import their California same-sex marriages back to their home states, creating additional lawsuits and legal pressures. New York Governor David Patterson has already stated that New York will recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states, at least in part to avoid costly lawsuits for the state. Unlike Canada, where the Supreme Court quickly ruled that there had to be a uniform national standard for marriages and it would not be acceptable to have gay marriage on an ad hoc basis depending on the whims of individual provincial courts, the US system is more decentralized and it is unlikely that the Supreme Court of the United States would enforce all states to recognize same-sex marriage on the basis of the precedent set in a few states (after all, there were still anti-sodomy laws on the books in several US states as late as 2003, when the Supreme Court finally did overturn the laws that remained in a 6-3 decision). However, there may be more successful legal challenges at the state level, leading state courts to overturn existing constitutional bans and ballot initiatives.

Finally, the California decisions adds one more observation to what now appears to be an inexorable trend across the globe – acceptance of the legitimacy of same-sex unions, and a further demand that the acceptance extend beyond mere legal rights to symbolic gestures such as the use of the word “marriage” itself. California and Massachusetts join the list of countries that have already legalized full same-sex marriage (including use of the word “marriage”) – the Netherlands (first to do so in 2000), Belgium, Canada, South Africa, Spain and Norway (beginning in 2009). The list of countries with civil unions and registered partnerships is much longer (Denmark was the first, all the way back in 1989), but in these countries the law is not settled as there may be a desire among gay-rights advocates to push for the symbolic recognition as well. As the California judges made clear in their decision, when it comes to recognition for a vulnerable minority that has suffered historical and current-day discrimination and prejudice, symbolism can be just as important as the concrete rights themselves.

I think the decision is just fantastic- how wonderful for couples that love each to be able to get married if they want to. I’ve read about some couples that have been together for 20, 30, 40 years, and now they can get married. I think it will be really disappointing if a law manages to pass that will once again ban marriage availability to all people. If it does, it will be another example of US governments in the Bush era just passing legislation to meet their own agendas after previous action has been ruled unconstitutional by a court. Judges must be getting frustrated, when they try to uphold constitutional rights, only to find them re-routed by a new piece of legislation.

Some protesters on the first day the marriage licences were granted were saying things along the lines of “what’s next? marriage to an animal or an object??!” Such comments are hardly valid ‘floodgates’ arguments, and demonstrate the problem of intolerance in society today- when people are equating a gay person with an animal or an object. As long as two people love each other, they should be allowed to celebrate their union. These couples that have been together for so long are a shining example in a world of divorce- and in fact, you could argue that they are proof that marriage itself is not a necessity for a long-term, stable, loving relationship. The essential ingredients are two people who love each other and are willing to commit and give their lives to each other, and that is wonderful.

And to finish my comment with a bit of humour, I just want to throw in a quote from Robin Williams’ character Tom Dobbs in the movie Man of the Year:

“The president wants to pass an amendment banning same-sex marriage. Anybody who’s been married knows it’s always the same sex!”