By Otto Spijkers

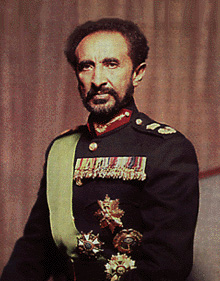

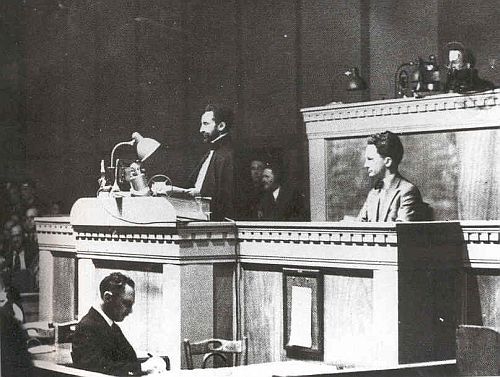

The gathering of the Assembly of the League of Nations in June-July, 1936, was the dramatic climax of the dispute between Italy and Ethiopia, at least as far as the League of Nations was involved. The Emperor of Ethiopia, in exile at that time, came in person to Geneva to address the Assembly, something no other (former) head of state had ever done. His speech became one of the most famous speeches in the history of the League.

The gathering of the Assembly of the League of Nations in June-July, 1936, was the dramatic climax of the dispute between Italy and Ethiopia, at least as far as the League of Nations was involved. The Emperor of Ethiopia, in exile at that time, came in person to Geneva to address the Assembly, something no other (former) head of state had ever done. His speech became one of the most famous speeches in the history of the League.

In his speech, the Emperor referred to the barbarism of the Italians in the way they fought the war in Ethiopia (the Italians used chemical weapons, such as mustard gas):

The deadly rain that fell from the aircraft made all those whom it touched fly shrieking with pain. All who drank the poisoned water or ate the infected food succumbed too, in dreadful suffering. In tens of thousands the victims of the Italian mustard gas fell. It was to denounce to the civilized world the tortures inflicted upon the Ethiopian people that I resolved to come to Geneva. (Translation. Proceedings of the Sixteenth League Assembly, held between June 30 – July 4, 1936.)

When you read this, it is difficult to believe Mussolini when he suggests, as he did in his victory speech cited in my earlier post, that the Italians saved the Ethiopian people from barbarism. Selassie then referred to the Council’s adoption of a report in October 1935 (see here for the text of the report and some remarks on the conflict by Ethiopia and Italy at the Council), which unambiguously concluded that Italy had invaded Ethiopia, committing aggression. What were the consequences of this conclusion, Selassie wonders openly:

The Ethiopian Government never expected other governments to shed their soldiers’ blood to defend the Covenant when their own immediately personal interests were not at stake. Ethiopian warriors asked only for means to defend themselves. On many occasions I asked for financial assistance for the purchase of arms. That assistance was constantly denied me. What, then, in practice, is the meaning of Article 16 of the Covenant and of collective security?

The Emperor does not ask his question solely in relation to the conflict between Ethiopia and Italy; he asks the question in a more general way:

I assert that the issue before the Assembly today is a much wider one. It is not merely a question of a settlement in the matter of Italian aggression. It is a question of collective security: of the very existence of the League; of the trust placed by States in international treaties; of the value of promises made to small States that their integrity and their independence shall be respected and ensured. It is a choice between the principle of the equality of States and the imposition upon small Powers of the bonds of vassalage. In a word, it is international morality that is at stake. Have treaty signatures a value only in so far as the signatory Powers have a personal, direct and immediate interest involved?

The Emperor foresaw what was indeed about to happen: various reform proposals were called for during the very same Assembly meeting. The proposals all aimed at making the Covenant more realistic, rather than making the world more idealistic. However, in the (idealistic?) view of the Emperor, it was not formal reform that was needed.

The Assembly will doubtless have before it proposals for reforming the Covenant and rendering the guarantee of collective security more effective. Is it the Covenant that needs reform? What undertakings can have any value if the will to fulfill them is lacking? It is international morality that is at stake, and not the Articles of the Covenant.

The United Nations Charter is a more realistic charter than the covenant, as it gives special privileges to those that in fact already enjoy these privileges: the superpowers. At the San Francisco Conference (for some more info, see here and here), where the UN Charter was drafted, the small nations acquiesced in giving the great powers a special status in the UN framework. However, with special powers come special responsibilities. As the Dutch delegate remarked:

The Netherlands Delegation fully realizes that in the present state of the international community, it may be necessary to invest certain powers with special rights if a new organization for the maintenance of peace and security is to be established at all. Such a position the great powers have in fact always enjoyed in the past. Now, however, this special status is going to be offi cially recognized and sanctioned. We believe this to be regrettable. Why? Because this new system legalizes the mastery of might which in international relations, when peace prevailed, has been universally deemed to be reprehensible. If, nevertheless, we acquiesce in giving the great powers this special status, we can only do so in the expectation that they will demonstrate in practice that they are conscious of the special duties and responsibilities which are now placed upon them. (UNCIO, vol. 11, 163-164.)

The question is: are the superpowers really conscious of the special duties and responsibilities placed upon them, or do they just benefit from their privileges (such as the veto in the Security Council)? – Otto